The Deep River Coal Field’s story spans centuries and includes the death of more than 130 men. Its past shines a light on racial histories in central North Carolina, labor standards, and the importance of energy independence for the growing republic.

In the following pages, the reader can learn more about the intersection of science, economics, and culture, that occurred in this now forgotten history.

However, before one can learn more about the history, it is helpful to just define the Deep River Coal Field – where is it, and why was it so important?

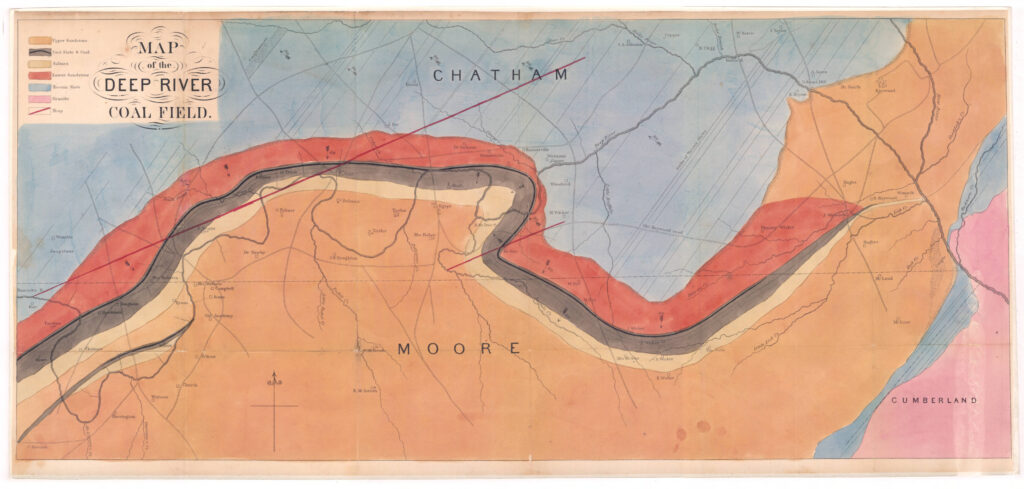

The field spans about 30 miles, from the north-eastern extent of Moore County, NC, and follows the Deep River, Lee, and Chatham County’s mutual border. The coal’s extent tapers just past the former village of Farmville, near present-day Cumnock NC. There are nine documented mines listed above, but two draw special emphasis. Cumnock (Egypt) and the Carolina (Farmville or Coal Glen) Mines are the region’s largest and most profitable mines.

Note the thickest (darker) bands are found around the communities of Gulf and Cumnock. Let’s take a trip underground and better understand what’s happening

Wilcox Iron Works: Coal’s Early Years

Europeans arrived in the lower Deep River Region in the 1750s, after moving along the Cape Fear River. Sparse in the beginning, the surrounding areas grew rapidly, and in 1771, the colonial government of North Carolina formed Chatham County, from lands formerly appropriated to Orange County. One settlement has withstood the test of time: Gulf (sometimes spelled as “Gulph”). This is the site of the state’s first iron works.

Founded by John Willcox on the southern side of the Deep River, the ironworks is just a short distance from the present-day Gulf Bridge. Whether by chance or by choice, Willcox’s Iron Works found itself near an outcropping – or surface deposit – of coal. Willcox’s furnace on the Deep would not stay his primary furnace – though it would continue to be his primary residence.

A second work built on Tick Creek, near the present-day community of Bonlee, NC, about ten miles north of the location in Gulf, would produce more ore during the late colonial period. More records exist detailing this latter location, in part because of the North Carolina provincial government’s interest in the works’ production. The provincial congress purchased the works prior to the Revolutionary War, but soon returned the mine to Willcox. These records prove useful because they provide insight into some of the tasks and people necessary to run this foundry.

Image of Census

Iron Labor

Forging iron is a laborious task. Furnaces heat the ore to meltingly hot temperatures. A large quantity of fuel is needed to accomplish these tasks. The needs of an iron works require a team, and in the case of the early work in Chatham County, the team consisted of enslaved labor. A House Report recorded in 1776 notes “That twelve slaves, including a woman and boy, are necessary for carrying on the Foundry. By 1777 the number of enslaved people working between the two furnaces (Gulf and Tick Creek) totaled seventeen individuals. In the 1790 census, just three years before Willcox’s death, Willcox enslaved eleven individuals, presumably people who labored either in the collection of coal or the running of the foundry.

Revolutionary Ore

The allure of colonial ore struck the colony to its core, and a battle over both mineral rights and holding ensued. The colonial government took great interest in the happenings at the Iron Works. In 1776, after the prospect of producing their own Iron Ore, the Council of Safety (a reporting division to the provincial congress) assigned James Mills to investigate the Iron Works for possible purchase. In addition to Mills, local commissioners joined the venture – individuals who represented the state while the foundry operated. This included Ambrose Ramsey, a prominent individual who lived further downstream of the Deep River.

On the eve of the revolutionary war, and on November 30, 1776, the legislature assigned Willcox the task of “casting of cannon, cannonballs, and grapeshot for the use of the state.” For the next two years, the state attempted to produce Iron at the Tick Creek and Gulf furnaces. However, the job required grueling and high quantities of laborers, with James Mills charging “twenty-five or thirty negro men are as few as can be carried on with.” Mills’ words to the provincial government remind us that only certain people could be expected to undertake the grueling work necessary not just for iron production but work necessary to support the country’s independence from Britain.

Willcox’s Later years

The foundries proved inefficient at producing enough munitions to serve the colonies to a satisfactory extent. By 1779, Wilcox once again owned the foundry. A flood destroyed the Deep River Works, and according to oral tradition, sometime in the early 1780s Wilcox rebuilt the works, about a quarter-mile north of the Deep River, near US 421 in Gulf. This new location sat much closer to the approximate location of John Willcox’s coal pit. This coal pit would be the first documented commercial attempt at using Deep River Coal.

Science and the Age of Coal Exploration

In 1826, Professor of Chemistry, Mineralogy, and Geology, Denison Olmstead began a clinical evaluation of the region, which later led to the exploration, extraction, and exploitation of coal for the next one hundred and fifty years.

Professor Denison Olmsted conducted the region’s first scientific take examining the resources beneath the surface. Commissioned by the Board of Agriculture, Olmsted’s survey explored Central North Carolina’s mineral holdings. These holdings included the Deep River Coal Field. During his visit to the former site of the Willcox Mine, Olmsted notes “[Willcox] took some pains to have it opened and introduce the Coal into use.” Additionally, Olmsted writes “Blacksmiths from different parts of Great Britain made trials of it and concurred in pronouncing it to be of excellent quality.” Not only is this an endorsement of regional coal, it reminds us that the industry is highly migratory, relying on the labor of chattel slavery, but the expertise from across an ocean.

The 1850’s: Coal’s Big Win

The 1850s are the regional flashpoint for the Lower Deep River. After the death of a local plantation owner, and enslaver, Peter Evans in 1851, the region appeared to take a larger commitment to export minerals. In response to the boom, multiple scientific reports examined the mineral and regional prospects. This scientific approach made one claim clear: the state must raise the coal sitting beneath the surface – it would simply be too valuable not to. In the following pages, I want to provide some information about the reports, including their key findings and if they encountered any challenges from others. See the abbreviated timeline below

1853

Walter R Johnson Report

Johnson’s report focuses on the eastern extent of the coalfield. With a focus on Evan’s lands in Egypt and the coal pits at Farmersville. Johnson spends a deal of time examining the geological properties of Farmersville Coal. He asserts that this Coal Bed on the North Side of the river is the place to beat. Included below is Charles Jackson’s Map of the region

1854

Charles R Jackson Report

Jackson examines the geological makeup of Deep River Coal. Though the region is largely bituminous (a secondary quality when compared to Anthracite), the prospect of use remains high. Jackson notes that the previous pits at Farmersville have expanded to a slope mine, with a perpendicular depth of “16 and 8/10th feet”

1856

Ebenezer Emmons

In 1856, State geologist Ebenezer Emmons’ report offered the first lengthy report since Olmstead’s writings. Emmons mentions the major stakeholders in the coal game – McIver, Evans, and Murchison. His choice here is important because it shows a selection of a few of the original companies finding profit, and the rest falling short. Emmons highlights the rapid expansion of the Egypt Mine, now at a depth of 460 feet.

Published in the same year, The North Carolina Standard reported on-site about the conditions of the mines. The paper’s article aids in reconstructing the development of mine between the gaps in the official reports. The paper reports on the open pits owned by the Haughton’s in Gulf, the pits [slopes] at Farmersville, and pits at the Taylor place. It also mentions the shaft in Egypt. Machinery pumped water out of the Egypt mine at a rate of “millions of gallons a day,” water accumulated by a slow, unending, drip. The paper also notes that forty-five men worked in the mines and the surrounding farm, twelve of which worked directly in the pits of the mines.

In the century after 1850, the Deep River Coal Field expanded and faltered on a regular basis. Many pits sat dormant, but two mines pressed on: Egypt and Farmville. Additionally, in 1857, Egypt experienced its first of many deadly disasters in the region. To learn more about the men killed in 1857, or the other mines in the region, visit the pages below